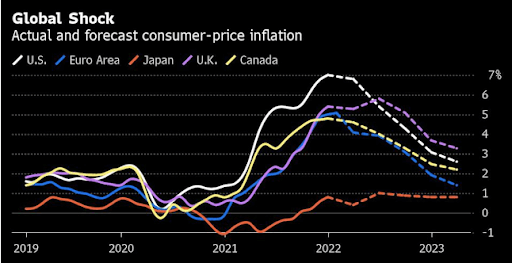

Goodbye Easy Money as Hawkish Central Banks Speed Up Rate Hikes

Feb 5, 2022

The era of easy money is drawing to a close.

Two years after the pandemic sent the global economy into a deep but brief recession, central bankers are withdrawing emergency assistance – and they're doing it far more quickly than either they or most investors anticipated.

The Federal Reserve of the United States is poised to hike interest rates in March, and last Friday's employment data fuelled concerns that the Fed will need to act swiftly. The Bank of England recently announced consecutive rate increases, and some of its officials desired to act even more firmly. The Bank of Canada is scheduled to begin operations next month. Later this year, the European Central Bank may join the fray.

Rates are increasing because policymakers believe that the global inflation shock now offers a greater danger to GDP than the further damage caused by Covid-19. According to others, they arrived at that decision far too late. Others worry that the hawkish shift may stymie recovery while providing little relief from high prices, given that a portion of the spike is due to supply constraints beyond the scope of monetary policy.

Among the world's largest economies, there are a few exceptions.

China's People's Bank looks to be heading in the opposite way. Credit is set to become more affordable as new viral outbreaks and a housing collapse cast doubt on the world's second-largest economy's future. And the Bank of Japan is anticipated to maintain its current policy course this year, but traders are beginning to doubt its ability to do so.

Numerous central banks in emerging economies began hiking rates last year – and they are not finished yet.

Brazil just increased its standard by 150 points for the third consecutive week, while the Czech Republic increased it to the highest level in the European Union. Russia, Poland, Mexico, and Peru may continue their tightening campaigns this week, despite the fact that some believe the Latin American cycle has peaked.

JPMorgan Chase & Co. economists anticipate that by April, rates will have increased in nations that collectively create almost half of the world's gross domestic product, up from 5% presently. They anticipate a worldwide average interest rate of approximately 2% by year's end – roughly the pre-pandemic level.

All of this implies that monetary policy will be tightened to the greatest extent since the 1990s. And the trend is not limited to interest rates. Central banks are also reducing the size of their bond-buying programs, which they used to keep long-term borrowing costs low. Bloomberg Economics projects that the Group of Seven nations' aggregate balance sheet will peak by mid-year.

"The situation has changed," economist Aditya Bhave of Bank of America Corp. said in a research on Friday. "Global inflation has accelerated central bank hike cycles and balance sheet contraction across the board."

By doing so, the shift may terminate a pandemic boom in financial markets that was exacerbated by easy money.

This year, the MSCI World Index of equities is down around 5%. Bond prices have plummeted globally, pushing yields higher.

The central bank's reassessment has been prompted by a surge of inflation. It is caused by a mismatch between growing demand in post-lockdown economies and supply shortages of some vital commodities, resources, and items – as well as employees.

The United States is projected to post 7.3 percent inflation for January this week, the highest level since the early 1980s. Inflation in the eurozone has just reached a record high.

Even a few months ago, the majority of authorities did not expect the predicament in which they now find themselves. They spent the most of 2021 claiming that pricing problems were "temporary." They applauded the strong recovery in employment and disregarded inflation fears raised by certain observers.

Now, policymakers have concluded that inflation is here to stay – and that allowing it risks igniting an upward spiral of prices and wages that may prove hard to control without precipitating a recession.

By moving immediately to calm the situation, they aim to achieve the famous "soft landing" rather than a crash.

Risks exist in both ways.

According to JPMorgan economists led by Bruce Kasman, inflation will likely continue to be fueled by reducing unemployment and increasing demand for services as economies demonstrate resilience to the omicron variant. "We find it difficult to reconcile continued low inflation with little central bank intervention," they added in a report.

Some prominent economists and investors warn that central banks are still "behind the curve" and are unaware of the magnitude of the actions that would be required.

However, quick rate increases now may be counterproductive if inflation does begin to decline as supply networks mend and commodities markets calm. This might result in policy settings appearing to be excessively restrictive – something that occurred to the ECB a decade ago.

And even if inflation persists, it may not be the type that can be handled by monetary policy.

BlackRock Inc. strategists think that prices are growing faster than expected due to supply constraints, and central bankers should accept this. According to Bloomberg Economics, if the BOE is serious about bringing inflation down to its target of 2% this year, it will have to boost rates by enough to put 1.2 million people out of work.

For the time being, the only direction for global rates is upward – but the details are murky.

Forecasts vary greatly on the number of Fed rate rises expected this year. While Barclays Plc anticipates just three hikes, Bank of America anticipates seven. Additionally, it is unknown how large the shifts will be, when they will occur, and where the benchmark rate will ultimately finish up.

Central bankers prefer that their aims are transparent. They now need to work out how to convey their new policies to investors, having made a sudden policy shift. Otherwise, markets may face turbulence.