Omicron Will Hurt the U.S. Economy. Why the Pain Won’t Last.

Dec 23, 2021

Over the last few weeks, the Omicron form has increased Covid-19 cases to record highs in cities across the United States, disrupting Christmas travel plans and pushing workers and consumers out of offices and stores.

However, although certain sectors of the economy are taking a hit — showing a decline in consumer demand or closing due to a labor shortage — others dismiss Omicron as little more than a blip on the radar. The mixed picture shows that, while the virus will almost surely exert a drag on economic growth, any longer-term effects are likely to be transient.

"Overall, our views on the economic outlook for the medium term have remained consistent," says Robert Rosener, senior US economist at Morgan Stanley. "However, this is presumably about a more significant near-term shift in the pattern of activity."

The reduction in activity for in-person services is already visible, particularly in large cities and densely populated areas where Omicron has expanded the fastest. According to payroll processor Gusto, employees at service-sector enterprises in New York witnessed an almost 23% decrease in average weekly hours worked between 28.2 to 21.8 hours between November and December. In the run-up to the winter holidays last year, average weekly hours jumped by roughly 18 percent, Gusto reported.

Since late November, when news of Omicron initially broke, the number of subway users in New York City has likewise been declining in comparison to pre-pandemic levels. According to Metropolitan Transportation Authority statistics, ridership was 74 percent of the 2019 average on Nov. 21, the Sunday before Thanksgiving, immediately following the discovery of Omicron. On Dec. 19, it had plummeted to 59% of its 2019 level.

According to data from the reservations-booking service OpenTable, the number of individuals dining in-person at restaurants fell 13% last week throughout the country. These rates stayed constant with 2019 levels for the week after Thanksgiving.

"Unfortunately, the economy appeared to be on the verge of normalizing," Constance Hunter, KPMG's chief economist, said in an email to Barron's. "However, Omicron is going to hold us back."

Due to the fact that the Covid rise is concentrated in large cities, which produce more economic activity, the short-term rippling effects on the broader economy may be more evident. While the coronavirus's Delta wave lowered growth by one or 1.5 percentage points this summer, the Omicron wave is expected to have a roughly two to three percentage point effect on growth in the first quarter, according to Scott Ruesterholz, a portfolio manager at Insight Investment.

However, other sectors of the economy continue to prosper, and experts believe that these solid underlying fundamentals may mitigate Omicron's consequences.

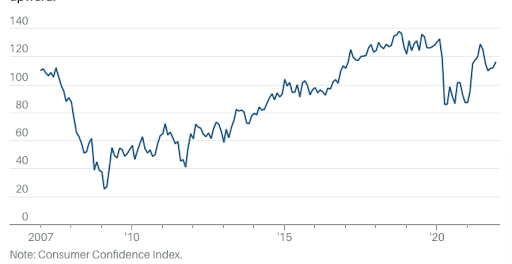

Consumers, for example, remain hopeful about the economy's future, despite the increase in Covid cases. The Conference Board announced on Wednesday that the Consumer Confidence Index climbed in December, as did the Expectations Index, which measures the short-term prognosis for income, company, and labor market conditions. Concerns regarding Covid, in particular, have also decreased.

Consumer confidence rose in December, and November's numbers were revised upward

Air travel patterns appear to be strong, with over two million passengers passing through airport security checkpoints on Monday, the fifth consecutive day of such volume, according to Transportation Security Administration data. And despite the increase in instances, the new film Spider-Man: No Way Home grossed $260 million at the box office last weekend, making it the second-highest-grossing opening ever.

The sustained strength of some service sector expenditures "does not imply we are out of the woods, nor does it mean we will see no impact," Rosener argues. "However, it fits with this general picture that, while the form of the influence on activity from each Covid wave has remained relatively constant over time, the size of the effect has tended to decrease."

Little is clear about Omicron's future course, including the duration of the current spike. And there are still huge dangers of a more severe economic effect if the crisis persists or worsens.

The virus's extreme contagiousness, for example, might overwhelm the United States' healthcare system. Increased fear of the virus alone has the potential to keep employees off the job and slow the labor market recovery, even in the absence of mandatory shutdowns. Additionally, any effects on labor supply, when combined with a possible increase in demand for products as consumers migrate away from services, might drive inflation higher.

"The reality is that we just do not know," says Megan Greene, a senior scholar at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government and chief economist at the Kroll Institute, a corporate investigations and risk consulting business.

However, one consequence is certain in the short term, regardless of the virus's next destination. "Even if we are simply experiencing uncertainty," Greene notes, "this is a drag on progress."