Wells Fargo’s $28 Billion Oil Lenders Are Ready for This Boom

Apr 21, 2022

A year after Wells Fargo & Co. became one of the last major U.S. banks to make a net-zero commitment, thereby putting its massive oil and gas lending business on the verge of extinction, the bankers who allocate billions of dollars to fossil resources aren't worried.

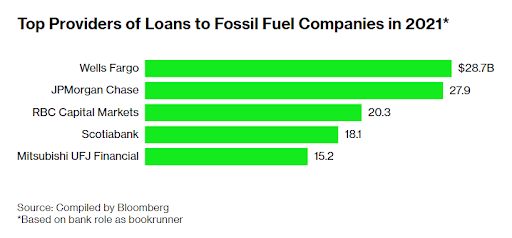

Oil and gas experts have endured a string of financially draining years, culminating in a devastating pandemic. Now, the fossil fuel industry is booming again, and Wells Fargo's lenders are at the very top. According to Bloomberg statistics, no one in the world allocated together more fossil energy loans as a bookrunner in the previous year. The bank's total commitment to the industry for 2021 exceeded $28 billion; it had made over $188 billion in hydrocarbon loans since late 2015 when the historic Paris Agreement was signed. That number is greater than the total market capitalizations of BP, Marathon Petroleum, and Valero Energy.

There are valid grounds for the heads of the fossil finance industry to be concerned, beginning with the bank's net-zero objective: Wells has followed more than 100 other banks in setting mid-century targets for reducing carbon emissions. Not many bankers want to work in a field that is essentially doomed for extinction. Even if you are skeptical of corporate commitments, the growth of ecological, socioeconomic, and governance considerations into a multi-trillion-dollar sector increases stress on those who sponsor hydrocarbon businesses.

However, Wells Fargo bankers are taking the long view. "There's this concept or dynamic that it's a light switch," explains Scott Warrender, project leader for energy and power. "In our opinion — and in fact — it will take a considerably longer time period."

According to conversations with ten current and former Wells Fargo employees, the bank's leaders will not stop providing fossil fuel loans while the businesses are actively asking for more and more of these. Few industry insiders know where things will go from here. Their stance toward the global warming situation ranges from pragmatism to, in the case of one former CEO, a dismissive attitude.

All of this creates a moment of high stakes for the energy sector, the warming planet, and Wall Street, particularly for a bank that CEO Charlie Scharf is attempting to turn around after years of scandals. Because access to cash is so vital to the fossil fuel sector, which spends a lot of money, the moral and financial considerations of bankers like those at Wells will be critical to the earth's climate future.

"Until the economy and society develops, we believe we need to support the broad energy industry in all its forms," Warrender says. As an energy banker for decades, he's seen the fossil energy business crash and then rebound into big-money booms. He endured the turmoil and learned to fight until the end, as he said more than a decade ago when he compared his career as an energy banker to his hobby of amateur boxing. Now, as he says, his interest has shifted to cycling, but his focus on energy remains the same.

"That's going to be intriguing," notes Derek Detring, who worked as a Wells energy banker before starting a business consulting the energy sector eight years ago. "Will investors stay away now that we're earning money again? It will be difficult for them to quit when the long-suffering sector returns to profitability," he argues.

Undoubtedly, oil prices skyrocketed following the Russia-Ukraine war and initiatives by the United States and the United Kingdom to boycott Russian oil. Energy CEOs and their bankers are prepared for turbulence. Wells Fargo's hydrocarbon lending has remained at the top of the market despite annual totals fluctuating—from $23.7 billion in 2016 to $48.3 billion in 2018 and falling down to $28.7 billion in the previous year.

Traditionally, bankers have not been under so much criticism from investors for not responding quickly on climate issues. However, this might change. In 2021, before the United Nations climate summit, Wells joined the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, an alliance of institutions and investment managers controlling $130 trillion in assets. In addition to resolving to eliminate emissions, the major banks have promised to start reporting for the carbon in their large assets someday. Developing standards for "financed emissions" will be a contentious topic, with activist groups keeping a close eye on developments. The investment company Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility requested Wells Fargo and other financial institutions in December to implement a program by the end of 2022 to guarantee that lending and underwriting do not lead to new hydrocarbon development.

For the time being, a Wall Street heavyweight may go green and ensure the future of renewable energy while also negotiating agreements on gas supplies and oil resources. Last year, Wells Fargo & Co. was barely ahead of JPMorgan Chase & Co. as the bookrunner on lending, which implies being the lead bank when other banks are involved. Loans provide a decent indication of how fossil energy corporations fund their businesses, but they also collaborate with Wall Street to sell bonds. Wells wasn't the top player in that market last year, with $7.7 billion under management, less than half of JPMorgan's $15.8 billion.

"For many years, we've been a key financial partner to conventional energy industries like fossil fuel companies and power utilities, as well as the developing renewables market," a Wells representative stated. We will continue to assist our clients in this sector as they provide society with the energy it needs today and cope with the changing market."

Hardly any of the institution's recent fossil energy financing agreements have been as large as the $5 billion revolving loans it arranged in 2018 for Energy Transfer LP, whose Dakota Access Pipeline is at the core of the conflict between the oil companies and the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. The head of the Dallas pipeline owner, billionaire Kelcy Warren, has a decades-long friendship with Wells. Not long before the loan, the consulting organization Institutional Shareholder Services Inc. suggested that Wells shareholders adopt a resolution seeking measures to assist Indigenous groups in their protection. In 2017, demonstrators marched to the California house of Tim Sloan, the bank's then-CEO, and installed an inflatable pipe.

That didn't deter Wells from continuing in the industry. Last year, it closed a $3 billion syndicated fossil energy loan with Enterprise Products Partners LP. In January, the Houston pipe operator decided to pay $3.25 billion in cash for Navitas Midstream Partners and its 1,750 miles of pipeline in the Permian Basin.

The narrative of fuel loans isn't only about climate change; it's also about consolidation, which has turned dozens of banks into just a handful. After a series of mergers, Wells Fargo became a fossil loan powerhouse. Tim Murray, a senior Wells energy executive until his retirement in 2005, had viewpoints that contradicted scientific opinion. "Instead of melting, the Arctic is actually growing," claims Murray, who went on to become the CEO of Guggenheim Partners and a Texas oil sector consultant. Arctic temperatures are rising more rapidly than the rest of the planet.

An energy-banking veteran from Texas has noticed Wall Street changing its stance on the environment. When oil and gas ruled the day, the answer would have been, "Yeah, I loaned to the industry, so what?". That's what we're supposed to do since we make a lot of money doing it.'" He says the answer is now more delicate. Banks that are sticking around are probably laughing up a storm as they face fewer competitors.

The energy transition presents opportunities on both sides - and sometimes, the same bankers are on the different sides as well. For example, under Warrender, Wells formed an energy development team last year to focus on developing renewable energy and charging infrastructure for electric vehicles.

There was a time about six years ago when the team looked different from what it does now. Herb Rakebrand worked on Wells' energy strategy team as a marketing strategist and project developer, where he felt out of place among Type A bankers. He described himself as a "nerd" among bank staffers.

David Marcell, a member of the acquisition and divestiture team during this time, saw things a bit differently. According to him, his co-workers were not belt-and-suspenders type guys. 'They worked hard for their clients and provided the best service they could."

While working for an exploration firm, Tyler Harris, who was a client of Wells, watched as banks rushed into this field as if nothing could go wrong. According to Harris, who is now an executive at Moriah Energy Investments LLC, no bank has ever lost money on oil and gas loans. The fierce competition allowed companies to pit lenders against each other. "People simply became lazy," he says. "It was a simple case of complacency."

OPEC played a big role in ending those easy times around Thanksgiving 2014 when the organization refused to reduce production. The industry and its bankers went into a long slump as a result of plunging prices.

Their hands were tied, in some ways. The bank could send an employee to your driveway if you failed to pay back a loan for a pickup truck. Assets related to oil and gas are riskier. "It isn't like poking a hole in the ground and finding oil coming out of it, and then everything is simply happy and bright," says Harris. Lenders waited for the market to recover before they approved loans. "They brushed it off," he says. "You need a waiver to last another six months? OK."

Wall Street has the power to shape the future of the energy sector

Some banks may have abandoned oil and gas due to years of poor returns. Five years after selling its energy lending unit to Wells, BNP Paribas SA, the French bank, announced it would cease doing business with companies involved in exploring, producing, or distributing shale gas or oil from tar sands.

Wall Street had an easier time turning its back on the energy sector when they were losing money on their loans, according to Buddy Clark, co-chair of energy at Haynes Boone's Houston offices. "But if prices rise to $100 a barrel and money is being printed by these oil companies, I can't imagine that the banks won't be back." It all suggests a pattern: "Prices are beginning to rise again, so the cycle begins again." In other words, just because ESG is "front and center" doesn't mean it will last forever. JPMorgan has set a $1 trillion green target for this decade, and Wells Fargo has committed $500 billion to sustainable finance.

In order to ensure that the ESG era lasts, Sierra Club's Adele Shraiman is coordinating the eco group's Fossil Free Finance campaign. "Wall Street's decisions about where to put their money can significantly influence the direction of our energy future," she says.

Banks are facing increasing pressure each week. A musician who took on Spotify over Covid-19 disinformation, Neil Young urged baby boomers to reject companies disrupting the global climate. Fans were urged to withdraw savings from JPMorgan, Citigroup Inc., Bank of America Corp., and Wells Fargo.

Nonetheless, it looks like the finance and fossil fuel industries are entering a particularly happy period in their relationship. Shale explorers, who have annoyed Wall Street by favoring expansion over investor returns for years, have finally announced that record cash flows will be returned to shareholders. It's drawn back investors at a time when oil prices have risen.

Former Wells executive Murray is optimistic regarding the prospects for energy lending in the future. "I believe the general public and Wall Street will eventually come to the same conclusion that we already have," he asserts. "We'll be here for a long time."