Expert Opinion: Economic Integration Was Supposed to Make the World More Peaceful. Why Did It Fail?

May 08, 2022

About the Expert : Christopher Smart is chief global strategist and head of the Barings Investment Institute.

When lifetime assumptions fall, it's humbling, but there are lessons to be found within the rubble. At least, that's my aim as I prepare for the next grueling phase of the Ukraine conflict and see the world's 11th-largest economy shrivel in front of my eyes. Most markets may be back to where they were before the war, but the globe is not. It's critical to understand why.

The basic concept of me as a portfolio manager was that investment in Russia produced strong returns while simultaneously bolstering progress on political reform and economic integration. The basic logic ran that increasing the country's involvement in the global economy increased the likelihood of political cooperation and peace. It's a central tenet of much Western diplomacy that merits a second look.

I wasn't so naive as to imagine that the "end of history" would usher in a new period of interstate trade, but the notion that economic participation stimulates ethical conduct made sense. As the benefits of German capital equipment, vacations in Turkey, and constantly growing living standards were apparent to a burgeoning Russian middle class. They would seek to support their country's broader interaction with the outside world. Sure, we'd still snarl at each other about NATO expansion or Middle Eastern wars, but the fundamental congruence of economic interests would keep the relationship on track.

It's a divisive concept in academics. "Realists" argue that the best way to understand international relations is for strong governments to impose their will on the weak. Indeed, this school believes it has been vindicated by the awful events happening in Ukraine. The premise that, in the aftermath of the Soviet collapse, the West overreached and failed to earn Moscow's trust has an obvious simplicity to it.

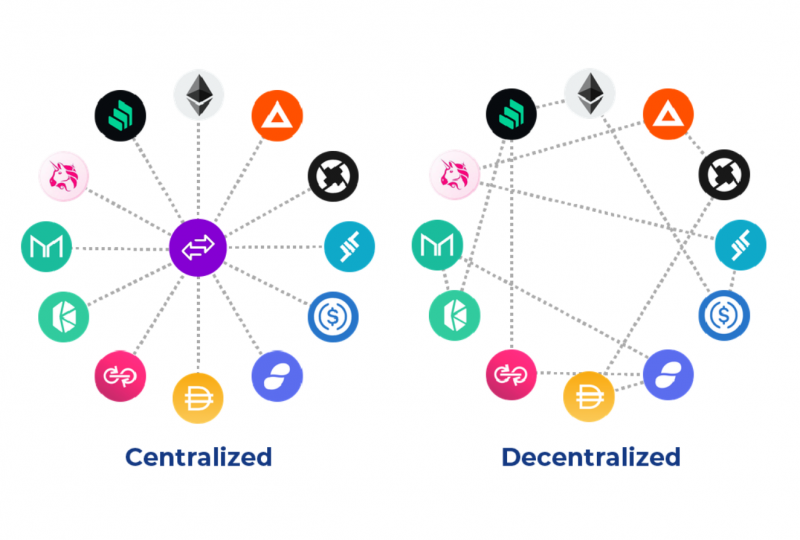

However, the idea that free-market democracies do not fight each other extends back to thinkers such as Immanuel Kant and Joseph Schumpeter. This was the crux of Western strategy toward post-Soviet Russia. Even though Boris Yeltsin had nothing to say about currency rates, there was a rush to get him admitted to the famous G7 meetings in the 1990s. There were armies of foreign consultants like myself whose governments funded initiatives to assist in the privatization of state assets, the creation of new corporate rules, and the founding of retail mutual funds. One important component of the approach was gaining Russian membership in the World Trade Organization in 2012. Trade numbers show that Russia's reliance on global business rose dramatically after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

During that period, the issues of contention (Serbia, Syria, Iraq, Snowden, Magnitsky, Navalny, and cyberattacks) swiftly swamped any shaky foundations for cooperation (tentative foreign investment, Afghanistan, and space).

By 2015, when Russia had conquered Crimea, I was part of a team at the National Security Council that began to intentionally undermine the economic connection, applying sanctions, discouraging business investment, and shutting off areas of collaboration. The new stunning round of penalties has dealt the ultimate blow to this strained economic relationship.

If this appears to be a catastrophic failure for one great experiment, it may serve as a catalyst for a rethinking of modern economic diplomacy.

First and foremost, we must examine why we failed. It's possible that the realists are correct in predicting that national security considerations will always take precedence. Or perhaps Russia is just the exception that proves the norm. Although free-market democracies may be more peaceful, the Putin government is neither. Would the world be here today if we had invested more in political and economic transition?

Second, we might have to reconsider how we balance economic participation with political or security considerations. The success of the European Union is based on trade and financial flows. However, we have used a similar "integration" policy with China, only to watch that relationship deteriorate. Despite the fact that India is a free market and a democracy, it remains one of the United States' most challenging allies on important foreign policy matters, including current Russia sanctions.

Third, at least in terms of Russia, we've entered a new period of economic diplomacy, relying on sticks to get outcomes where carrots failed. Extreme sanctions have yet to show effects in Iran, although they did eventually lead to post-apartheid South Africa's democratization and international integration. The punishment meted out will drive the Russian economy into a tailspin, relegating it to the isolation of the 1970s. Some measures may be loosened while negotiations for a cease-fire in Ukraine continue, but the true rationale at this point is to cause enough pain to urge regime change. This might happen rapidly or never.

As historians investigate these and other issues, perhaps the most obvious conclusion is that good economic involvement is required to achieve cooperative conduct from another country, but it is far from adequate. That may not appear to be much, but trying to redefine a major premise in Western strategy may be the best we can do for the time being while we pick up the pieces from our previous assumptions about Russia.

If you want to suggest your news and share your professional comments for commercial offers DM us: [email protected]