Less Money As Money Supply Shrinks. What Does It Mean For The World’s Inflation?

Jan 25, 2023

In the next few weeks, the Federal Reserve will make a critical decision. Markets expect the central bank to raise interest rates by a quarter of a percentage point, signaling a significant slowdown in record growth.

If that happens, a change in direction would be warranted, as higher rates seem to be working. The annual inflation rate fell for the sixth straight month in December, and it appears to be slowing further.

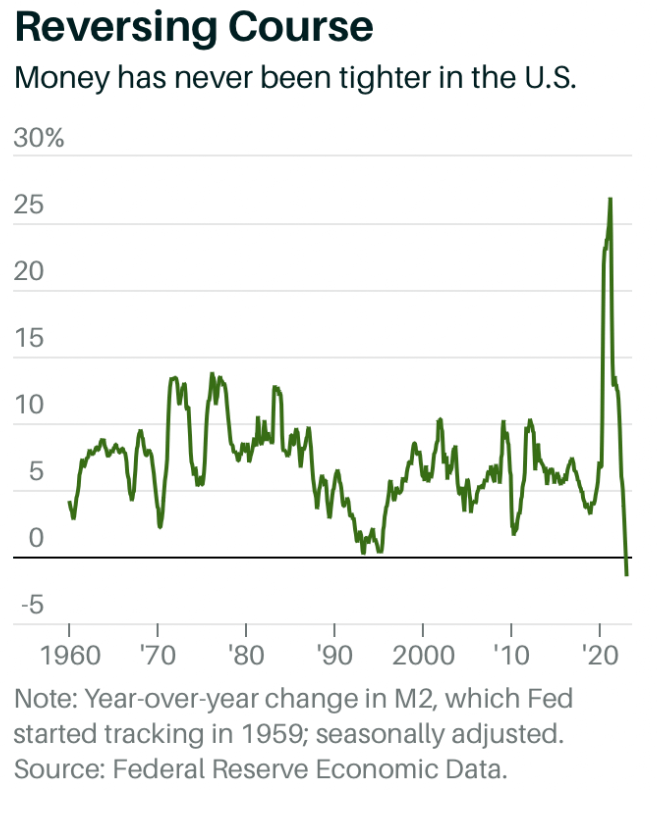

Another indication that the Fed's rate rises are having an effect: In December, the amount of money in the economy decreased. The growth of M2, a measure of the economy's money supply that comprises currency in circulation, balances in retail money-market funds, and savings deposits, among other things, has declined during the previous two years following a jump in 2020, but December figures show a decrease.

The December money supply growth rate was minus 1.3% as compared to a year earlier, the lowest ever and the first-ever decrease in M2 based on all available data. In 1959, the Fed began measuring the statistic. The rate of increase in November was already 0.01%, significantly below the record of 27% in February 2021.

This drop indicates a weakening economy and a significant impact of rising interest rates, which supports current recession forecasts. However, the statistics do not indicate a significant economic slowdown. Despite one of the strongest slowdowns, M2 is still 37% higher than before the epidemic. In other words, analysts believe that the amount of liquidity in the system remains large, indicating that more needs to be done to normalize the economy.

That isn't the only reason M2 rose — and has now fallen precipitously. We can look at the Fed's balance sheet operations to help us with this.

During the epidemic, the Fed's "quantitative easing," or bond purchasing, boosted the economy and the central bank's balance sheet to about $9 trillion.The Fed is decreasing liquidity by reducing its total assets through quantitative tightening.

The Fed's total assets were down 5.3% on January 18 compared to last year's peak, but the balance sheet is still more than twice what it was in February 2020 before the epidemic began. That's a lot of money, but the Fed doesn't want to risk upsetting financial markets by tightening further.

The Fed “does not want to convert monetary tightening into an episode of financial instability,” said Acharya, who along with three other economists published a paper in August titled Why Shrinking Central Bank Balance Sheets is an Uphill Task.

Finally, when M2 falls more, it should assist in tempering inflation by crimping demand and lowering the capacity to support bank loans and other financing for families, enterprises, and financial market transactions, according to Nathan Sheets, Citi's global chief economist.

However, investors should not assume that falling M2 always indicates an economic downturn, notes Richard Farr of Merion Capital Group. M2 has to decline by at least another trillion dollars to be meaningful, according to him.

Well, that's still quite a ways away.