Traders Believe the Fed Will Ease Policy Soon. Let’s Hope They’re Mistaken.

Mar 27, 2023

Former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke is unlikely to raise a glass to commemorate the anniversary of his March 28, 2007, assertion that the subprime mortgage crisis is likely to be contained.

That's not meant to pile on, especially since his successors, Jerome Powell, the current Fed chairman, and Janet Yellen, the previous Fed chair and now Treasury secretary, have spent the last two weeks scrambling to contain the crisis triggered by the failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank.

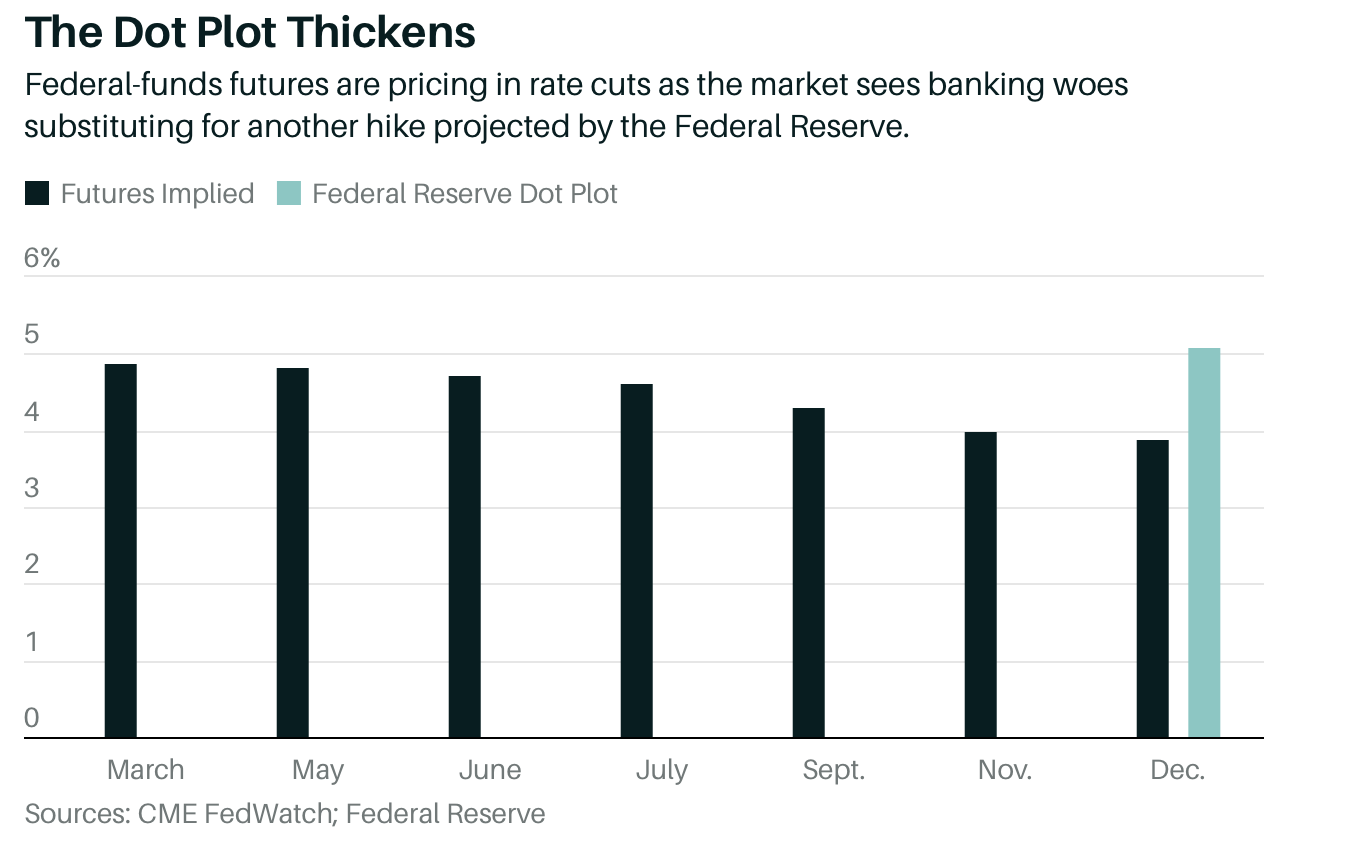

But, interest-rate markets are betting heavily that the country's central bank would reverse direction and dramatically relax policy to limit or mitigate the impact of continued bank troubles. This is reflected in futures contracts for the federal funds rate, which suggests that traders predict no more rises following the quarter-point increase this week. In fact, they anticipate layoffs as early as June. This situation would create new hazards.

After measures by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Treasury, and the Fed to boost bank trust, Powell claimed at a news conference on Wednesday that all depositors' money and the banking system are safe. He remarked after the Federal Open Market Committee announced the latest quarter-point increase in its main policy rate, increasing it to 4.75%-5.00%.

When Yellen told a Senate committee at the same time that "blanket assurances" were not being discussed, the effect was nullified. On Wednesday afternoon, markets plummeted as a result. The next day, though, she added a statement before a House subcommittee that they would be willing to take more steps if necessary.

Given all the crisis management experience she and other former and current Fed and Treasury officials have, one would assume that Washington has contingency plans. While they all often occur after periods of Fed policy tightening, each financial crisis has its unique characteristics when seemingly safe bets go awry. This time it was supposedly safe Treasury and agency mortgage-backed securities that lost value as interest rates rose, unlike the risky subprime mortgage derivatives in the previous case.

For those seeking historical antecedents, the first major post war financial crisis, the 1966 credit crunch, maybe the finest.

Banks and thrift institutions saw a deposit flight during the time, limiting their ability to issue loans. Yet, unlike the SVB run by its tech bro depositors, who withdrew millions with a tap on their phones, the deposit withdrawals almost six decades ago were the consequence of intentional Fed steps to calm the economy and inflation.

In the distant past, authorities restricted the interest rates of banks and other depositories under a rule known as Regulation Q. The Fed hiked market rates in 1966 to slow bank lending growth but did not raise Reg Q rates for bank accounts. As a result, depositors withdraw funds in search of higher returns, spawning a new, unappealing term:“disintermediation”—the flow of money away from financial intermediaries such as banks. As a result, banks had to curb lending or sell assets, in that case municipal bonds, resulting in a credit crunch in the summer of 1966.

The Fed had softened by late autumn, bank credit had resumed its expansion, and the crisis had subsided.

According to the St. Louis Fed's estimate of the era, the economy slowed dramatically from the delayed effects of the credit crisis, from a sizzling 8% rate in the fourth quarter of 1966 to 2% in the first quarter of 1967. And inflation would soar uncontrollably, reaching 4.5% in the fourth quarter of 1967, up from 3.2% the previous year. Although a recession would be avoided, inflation would reach double digits over the next decade.

According to Steven Blitz, chief US economist for TS Lombard, disintermediation has been reintroduced as a growth governor. Banks are subject to an asset crisis, which is exacerbated by decreases in their securities holdings. He believes that this will limit bank lending and, as a result, cause a recession.

But, the Fed is taking a risk by relying on reduced lending to restrict growth while limiting the increase in its real federal-funds target — that is, how much it surpasses inflation — to approximately 0.5%, according to Blitz. It is the central bank's anticipated neutral fed-funds rate — the rate at which the economy will neither stimulate nor constrain.

In the past, restrictive policies based on positive real interest rates were needed to control inflation. The current financial problems are expected to affect the economy, similar to an increase in the federal funds rate by half a point or more.

The good news is that the latest Fed data point to a stabilization, if not a complete containment of the crisis. As of Wednesday, the Fed had lent $354 billion to banks through its various lending institutions, $36 billion more than the previous week.

One source of comfort was a $42.6 billion decline in banks' normal discount window borrowing to a still-high $110.2 billion. At the same time, utilization of the new Bank Term Financing Program (under which banks can borrow against securities that have decreased in value for one year at par) increased by $1.7 billion to $53.7 billion. Credit extensions to FDIC bridge banks (those that can manage an insolvent bank until a buyer is found or another action is taken) increased by $37 billion to $179.8 billion.

But, banks do not appear to be searching for liquidity in general, and part of the borrowing witnessed last week was probably proactive, according to a client note released late Thursday by J.P. Morgan's fixed-income analysts.

Investors are still nervous about the possibility of bank contagion, both in the United States and abroad. The greater danger is that, as in 1966, the Fed may abandon its inflationary war prematurely in the face of a confidence crisis.