3 Emerging Markets That Are Better Choices Than China

Sep 15, 2022

Rising interest rates in the United States and Europe, a stronger dollar, and a turbulent market that makes investors wary of taking risks are often bad news for developing markets. However, a handful is holding up rather well and is likely to beat developed markets.

When the Federal Reserve hikes interest rates in the past, emerging markets suffered. Countries that borrowed significantly in dollars risk increased debt loads and a weaker currency in order to fund their obligations. As rates increase abroad, capital tends to fly to safer areas, tightening financial conditions and intensifying the misery.

That is still the case in a few unstable emerging markets, such as Turkey, Colombia, and South Africa. However, as Barron's observed earlier this year, more developing markets are in a better position this time.

Strong demand for oil and commodities like copper and nickel benefits commodity producers like Indonesia. Emerging market central bankers like Brazil's have been more aggressive in combating inflation than the Federal Reserve. Structured trends, such as tensions between the United States and China and the conflict in Ukraine, help nations such as India and Indonesia.

At 10.5 times next year's profits, the MSCI Emerging Markets index is cheaper than the 14 times it has averaged since 2010. With the epidemic, emerging markets have traded at their lowest valuations in relation to developed markets since the global financial crisis. Part of the discount originates from China's lengthy list of problems, which contributes to over a third of the MSCI index, as it deals with a property collapse and a zero-Covid strategy that has imprisoned millions of people in big cities.

Optimists believe that China will continue to offer stimulus and lighten up on its Covid lockdowns following the 20th Party Congress in October when top leadership will be chosen – actions required for Chinese markets to rebound appreciably.

However, certain emerging markets are already appealing. Brazil, India, and Indonesia are poised to excel because their economic conditions provide an appealing counterpoint to the issues confronting the United States and China.

While the United States and Europe are still suffering the effects of increasing prices, Brazil concluded last year as one of the worst-performing economies, battling double-digit inflation. Earnings for corporations have suffered.

Brazil's central bank boosted interest rates from 2% in early 2021 to 13.75% in the last 18 months. This has put it far ahead of its competitors in the United States and Europe, and it is nearing the conclusion of its rate hiking cycle, with likely rate cuts later this year or next.

This would create the stage for values to rebound while increasing rates impact valuations in the United States and Europe, according to Todd McClone, co-manager of the William Blair Emerging Markets Growth fund, which has lately purchased more Brazilian shares.

Five Investments for Emerging Markets Recovery

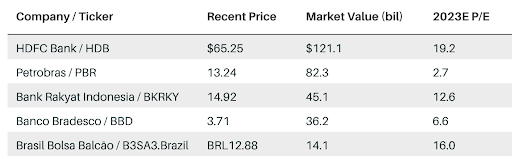

Brazil's stock market operator, Brasil Bolsa, is one method to profit from the country's better outlook. "As interest rates fall, equities should rise, and there will be more secondary and first public offerings," McClone predicts. "Because Brazil has a private-equity mentality, we might see more IPOs."

GQG Partners Chairman and Chief Investment Officer Rajiv Jain supports energy, minerals, and financial businesses as Brazil's outlook improves, including oil giant Petrobras and Banco Bradesco. The bank is trading at 6.6 times profits in 2023 and has a 16% return on equity. Jain believes it can provide a dividend yield of more than 7%.

"There is a risk of nonperforming loans due to rising rates," Jain adds, "but [the industry] is not coming off a time of wild lending in this cycle as it did in 2013 to 2014." He anticipates that such loans would "increase but not skyrocket."

Stocks to Take into Account for Exposure to Brazil, India, and Indonesia

Brazil's presidential election in October may cause unrest. Former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, a socialist, is predicted to defeat President Jair Bolsonaro. The market is already prepping for a Lula triumph at present prices. According to McClone, an upset by Bolsonaro would strengthen markets.

In the long run, the country will gain from the energy transformation. Brazil is well-known for its oil production. More surprising, according to TS Lombard, is that about 85% of its installed power-generation capacity is renewable, including hydro and wind—the highest among the Group of 20 nations.

Indonesia is also well positioned to benefit from increased commodity demand, particularly as countries seek alternatives to Russia's nickel and oil. Demand for its metals and palm oil has helped it achieve a record current-account surplus, which has kept the rupiah relatively robust. Its resources, many of which are required for green-energy goods, position it well for the long run.

The bull argument for Indonesia in the near run is that the economy is reopening as Covid restrictions are relaxed. Retailers are in a good position for a rebound, according to Laura Geritz, co-manager of the Rondure New World fund, which is overweight Indonesia and owns Ace Hardware Indonesia.

While Indonesia has been one of the best-performing markets this year, McClone, who has a larger allocation to the nation than peers, believes there is still room for development, adding that Indonesian firms are predicted to post 30% profits growth in the following year. McClone's fund owns firms such as Bank Rakyat Indonesia, a microfinance lender with a 30% return on equity, and United Tractors, which distributes coal mining equipment and is witnessing increasing demand as a result of the Ukraine conflict.

Indonesia and India are also well positioned to capture market share from China in the global supply chain as US-China tensions rise and corporations seek to diversify output, particularly in areas such as technology, medical equipment, and high-end manufacturing.

If there is an emerging country that fund managers believe will take China's place in the asset class, it is India, which Capital Economics predicts will be the world's third-largest economy by 2030. In recent months, foreign investors have become net purchasers of Indian equities.

While China struggles to get out of its economic rut, India is emerging from a decades-long slump after years of dealing with a debt crisis and short-term pain from major structural reforms, including tax reform and demonetization, which invalidated 85% of the currency in circulation overnight in 2016 in an effort to combat tax evasion and corruption.

India's business and bank balance sheets are in the best shape in over a decade. The gradual improvements are now "repowering India," according to Justin Leverenz, manager of the Invesco Developing Markets fund, which has a fifth of its portfolio in India.

He sees a tsunami of digitalization and formalization sweeping over India's informal sector. In addition, India is on the verge of a housing and credit growth rebound, in contrast to China, which is still reeling from a property market crisis.

McClone of William Blair is looking for chances in HDFC Bank, which he calls as "the JPMorgan Chase of India," as well as tile producer Kajaria Ceramics and property developers such as Oberoi Realty, which is ideally positioned for a housing rebound.

India is one of the most expensive developing market countries. It also imports energy, requiring around 1.1 billion barrels of oil each year. While energy costs have fallen from their highs, McClone believes a $10 increase in oil prices would harm the country's budgetary condition and impede its planned economic growth of 7.4% this year, as predicted by the International Monetary Fund.

Before the Ukraine crisis, Russia supplied around 5% of its energy needs; now, that figure has risen to 20%—and that oil is offered at a 20% discount, according to McClone. Policymakers are also bolstering the currency by drawing on $50 billion in reserves. Further deterioration is a danger, although India still has over $560 billion in reserves.

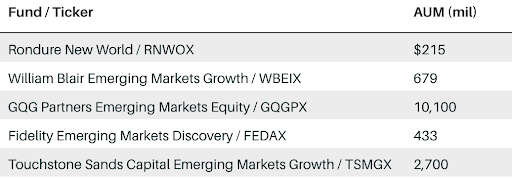

India, Indonesia, and Brazil make for less than a fifth of the overall developing market index. Some active funds have more aggressive allocations, such as Jain's GQG Partners Emerging Markets Equity fund, which holds a quarter of its assets in India, 18% in Brazil, and over 2% in Indonesia. McClone's William Blair Emerging Markets Growth fund has a 21% holding in India, a 6% holding in Indonesia, and a 5.6% holding in Brazil.

Other funds with strong track records and greater exposure to at least two of the three markets include Rondure New World, which has 17% allocated to India, 8% allocated to Indonesia, and 3% allocated to Brazil, and Touchstone Sands Capital Emerging Markets Growth, which has 11% allocated to Brazil, nearly 31% allocated to India, and 3% allocated to Indonesia. According to Morningstar Direct, Fidelity Emerging Markets Discovery has around 9% invested in Brazil, 19% in India, and 4.5% in Indonesia.

Given the sharp movements in currencies, with the yen and euro falling to multi-decade lows versus the dollar, Jain sees more macroeconomic risk in developed markets such as Japan and Europe, which are dealing with high levels of leverage, lax fiscal discipline, and anemic growth prospects, than in emerging markets such as India, Indonesia, and Brazil.

While developing economies are not immune to the concerns affecting the US and other markets, some of these nations are deviating from the trends in the US and Europe. That is cause enough to investigate more.